Maybe your first question is: what are probiotics? Good question. We’ll get into that. For simplicity’s sake, the probiotics we’re discussing are good microbes that we eat.

If you take a look at a grocery store shelf, it’s obvious that probiotics are having a moment. But for all their modern-day trendiness, they had a slow start. They’ve been a part of human life for thousands of years, but nobody knew about them until about 150 years ago. And it took until the 1990’s for scientists to start researching them in earnest. Now, just 30 years later, not only do we know more about probiotics… we’re actually creating completely new probiotics, with incredible new functions.

The question is... how did we get here?

1. Fermented foods

What foods have probiotics?

In the beginning, there was yogurt.

Long before we could identify probiotic microbes with microscopes, people were eating fermented foods. Beer, wine, yogurt, cheese, kefir, etc. Fermentation wasn’t just tasty; it was also known to be healthy. In a telling example dear to our hearts, ancient Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder would often prescribe fermented milk as a treatment for intestinal problems (citation), never knowing why or how it worked.

And for tens of thousands of years, this is where we were: unknowingly using fermented foods to supplement our diet with probiotics.

2. Crude probiotics

Who started the probiotic trend?

Elie and the Bulgarians: The birth of an industry.

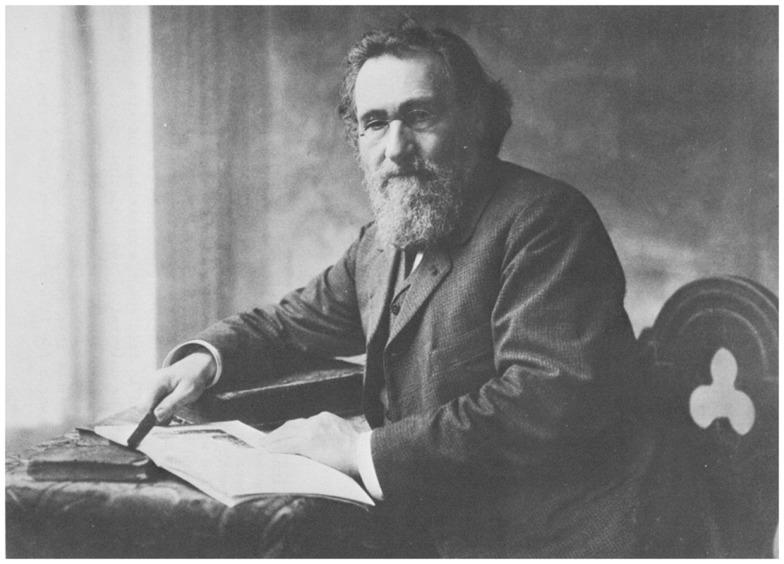

Every field has its fearless creator. For us, it’s 19th-century scientist Ilya Ilyich Metchnikoff, the Nobel Prize-winner, director of the Pasteur Institute, and, in some circles, the grand-daddy of probiotics – a.k.a., our boy Elie.

During his travels across the Balkans in the late 1800's, Elie noticed that rural people in Bulgaria, despite a brutal climate and extreme poverty, lived much longer than rich European city-dwellers (many over the age of 100). After researching the modest daily lives of these people, Elie concluded that the X-factor in their lifestyle was a good bacteria found in the “soured milk” that was a staple of their diet (citation).

Elie used his conclusion to prescribe a treatment for old age: eating soured milk (a.k.a. yogurt) or alternatively by skipping the food all together and simply eating more of the good bacteria he found in it.

With that, the first intentional probiotic was born! It was a turning point. From then on, people have been all about eating probiotics – good microbes – to benefit their health.

Probiotic drinks. Probiotic supplements. Probiotic whatever.

But like Elie’s experience with L. bulgaricus, these probiotics are eaten without knowing much about them. Even today, people still don’t know the specific type (the “strain”), behavior, or purpose of many of the probiotics we encounter.

Why? Well, with all due respect to Elie, most serious microbiologists just didn’t care enough to focus on researching probiotic microbes. Instead, they were researching bad microbes – the ones that cause disease. The result was that early probiotics products just weren’t scientifically backed. It was a sad state of affairs.

But thankfully, things have changed.*

*(Well, kind of. There are still a bunch of crude, nonscientific probiotics out there. Most of the products at the grocery store are this way, actually. But things are changing!)

3. Modern probiotics

How do we use probiotics today?

Scientists weigh in, and probiotics get smarter.

In the 1990’s, a new generation of scientists, armed with better technology and an appetite for new ideas, began researching the gut microbiome – the community of microbes living in our GI tract. They started to understand much more about how the microbes we eat interact with our bodies.

With more understanding came more respect for their potential, and more research dollars. In 2001, the World Health Organization (the “WHO”) at long last issued a formal definition of probiotics, kickstarting even more research. This led to a series of microbial discoveries that rocked the probiotic world….

We learned how to more accurately identify microbial strains and to evaluate how each strain interacts with the body. We learned that many microbes used as probiotics don’t even make it to the gut alive, but instead die when they encounter stomach acid, and that some microbes need extra “food” in the form of prebiotic fiber to thrive. And we learned that too many of some species/strains of microbes in your gut actually isn’t a good thing, but can instead be bad for your health.

With more scientific understanding, some folks in the probiotics industry took note and adapted. You’ll know which probiotic products did adapt because they do things differently, like

- Fully identifying probiotic strains (like “B. subtilis ZB183”) on packaging;

- Promoting survival through the gut by encapsulating against stomach acid or picking microbes known to naturally survive the trip;

- Including prebiotics in probiotic formulations to promote other good gut microbes; and

- Ceasing the “more is better” vision of probiotics and removing misleading labels touting “Billions of CFU’s!”

This incorporation of real science into some probiotic products has been a huge victory. And although these modern probiotics still represent a minority in the sea of crude probiotic products on the market, they are a significant step in the right direction.

4. Enhanced probiotics

What is the future of probiotics?

But one thing didn’t change with modern probiotics: the intended goal – why people take probiotics in the first place. Ever since the days of Elie, crude and modern probiotics alike have promised the same thing: generic, catch-all benefits like “gut wellness” and “digestive health.”

These benefits are so very subjective (who knows what “gut wellness” means, anyway?) that they provide cover for a multitude of probiotic products that don’t do much of anything.

We may know more about how to keep probiotics alive in the gut or how to keep them from hurting us, but we still don’t know whether any particular modern or crude probiotic actually works. Because “works” means nothing.

But things are changing (for real this time).

Recently a newer generation of scientists have started asking a new question: can we make probiotics do more? Can we use probiotics as tools to provide specific benefits, in ways prior generations could never have imagined?

We now know the answer to that question is a definitive – and exhilarating – YES.

The key lies in probiotic engineering – genetic engineering, to be precise. It’s the ability of scientists to create new microbes – and new probiotics – according to our own design. Using genetic engineering, for the first time ever we can now create enhanced probiotics that perform specific tasks.

Tasks like:

- breaking down particular toxins you encounter when eating things like dairy, alcohol, or bread

- providing new defensive capabilities to your gut, like the ability to block the absorption of lead or mercury.

- producing essential and healthy nutrients in forms your body can digest; and

- augmenting your body’s ability to respond to things like radiation or disease.

These benefits are far more tangible than generic promises of gut wellness. And what’s more, they’re more verifiable. We can tell whether or not an engineered probiotic works, because we know what it’s supposed to do. If we want to test whether it breaks down a toxin, the answer to that question is a simple laboratory experiment away.

And if a probiotic strain we engineered doesn’t perform as intended, we can fix it. We don’t need to go search for another probiotic out in the wild. Instead, we simply create a new probiotic – or a hundred new probiotics – and engineer and test them until we have one that works to provide the specific benefit we’re looking for.

This is what we – the folks behind ZBiotics™ – are working on: enhanced probiotics, built using genetic engineering. And we’re not the only ones. Other companies are doing the same thing, targeting everything from IBD to cancer.

In this new reality, we’re not tied down by how probiotics worked (or didn’t work) in the past. It’s the potential of probiotics that’s inspiring: all they can be when combined with the latest scientific research and our own creativity.

It’s a new vision for probiotics. And not to get sappy, but in the (probable) words of our boy Elie, it’s pretty awesome.